Quantum Computing, Braids, and Modular Categories

We introduce anyons, a hypothetical unit of computation in topological quantum computation. We explain their topological properties and discuss their relationship with modular categories.

Introduction

Quantum computing (QC) is an exciting new paradigm of computation, promising exponential speedup from state-of-the-art classical algorithms in certain computing tasks. Despite vigorous research from all sides of the task, obstacles to a quantum computer architecture that is scalable and tolerant to errors remain hard to overcome.

Qubits in existing models of quantum computation (such as trapped-ion models) are sensitive to their environment. Such sensitivities of the environment make qubits liable to introducing noise that dominates the computation we’d like to measure. To ensure we can recover usable data, we’d (approximately) need on the order of thousands of physical qubits per logical qubit to near-guarantee our computation is correct. This would be no issue if current QC implementations were highly scalable, but they are not. Topological quantum computing is a theoretical basis to address both these issues simultaneously.

Anyons and their statistics

While traditional QC implementations use bosons and fermions for qubits, topological quantum computing (TQC) uses anyons. Recall that two bosons exchange in a wave function causing a global phase shift \( +1 \) (i.e. \( | \varphi_1 \varphi_2 \rangle = | \varphi_2 \varphi_1 \rangle\)). Conversely, fermions exchange with a global phase shift \( -1 \), so \( | \varphi_1 \varphi_2 \rangle = - | \varphi_2 \varphi_1 \rangle \). Anyons are type of quasiparticle that allow for more general phase shifts \( e^{i\theta} \) for some value of \( \theta \). We recover bosons and fermions at \( \theta= 0 \) and \( \theta=\pi \), respectively. Anyons can take any statistics between Bose-Einstein statistics and Fermi-Dirac statistics and beyond, corresponding to values \( 0 \leqslant \theta \leqslant 2\pi \).

I’ve somewhat lied by omission in the previous paragraph. The global phase shifts corresponding to \( e^{i\theta} \) are actually relevant to the so-called abelian anyons. One can generalize this phase shift further to an even larger class of unitary operators satisfying the Yang-Baxter equation; such quasiparticles are non-abelian anyons. These non-abelian anyons are the building blocks to encoding information in TQC. The question remains–what does this buy us? I’ve already alluded to how TQC may be less sensitive to environmental noise than classical qubits, so we should understand how.

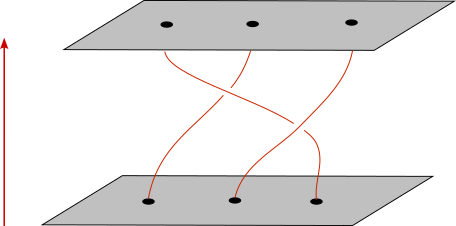

Figure 1: Inequivalent exchanges for identical anyons.

When thinking about how anyons interact with each other, we must think topologically. That is, we can do everything up to a “smooth/continuous” deformation. In one dimension of space, nothing interesting can happen: we cannot exchange anyons at all. In three dimensions of space, everything is trivial. If an anyon moves around another anyon back to its starting position, one can “drag” the path and shrink it simultaneously, so that topologically the path is indistinguishable from the particle not moving at all.

In two dimensions of space, things get more interesting. In a flatland with two particles, there are two topologically distinct paths a particle can take in the plane. They are illustrated in Figure 1. In fact, there are infinitely many: one can wind a particle around the other as many times as needed to produce a path distinct from the others.

Figure 2: Braids on n=3 strands traced out over time progression.

At each slice of time, the position of anyons in flatland correspond to points in a plane. As we progress time, the trajectories of the anyons trace out paths akin to strands of string. The strings cannot cross through each other, as this would mean the particles “collide” at some point in time. Figure 2 illustrates this phenomenon, with the arrow indicating the passage of time.

Mathematically, the collection of all these trajectories for some fixed \( n \) particles–disallowing the strands doubling back–form a group under composition: it is the braid group on \( n \) strands, denoted \( \mathcal{B}_n \). Here, the braid group is an instance of a more general kind of group called a motion group. The mathematical formulation of this is to say that the braid group on \( n \) strands is the motion group of a disjoint union of points embedded in a compact box. More general motion groups corresponding exist, such as motions of circles or trefoils in a compact box. These are quite a bit more complicated, and we know little about them compared to the braid groups.

To each braiding we want to associate a unitary operator (read: a quantum gate), so we can say that mathematically, the statistics of \( n \) anyons correspond to certain unitary representations \( \mathcal{B}_n \to U(V) \) of the braid group on \( n \) strands. From a practical perspective, the act of applying a quantum gate to a system of anyons would correspond to braiding them. This basis for computing is intuitively less sensitive to environmental noise in the sense that the topological properties of braids are more stable under small perturbation. One can imagine that it is easier for a ball to bump into a wall from a slight gust of wind than to rearrange two crossed strings so that the lower string lies on top by cutting and rearranging. This comparison is not unlike the difference between the sensitivity of qubits in the classical QC world and the TQC world. Study of braid groups, motion groups, and the unitary representations of these groups shed light on the behavior of anyons, making it a subject of physical interest, and not just one of intrinsic beauty.

Modular Categories

We switch gears a bit to discuss the other data of anyon systems, of which there is many. The study of braids and their unitary representations will capture how the interactions of anyons in space alter the data of the global quantum system, but says nothing of the data internal to the particles, and how that data changes.

Anyons carry lots of intrinsic data. One can formalize the physics of anyons along with certain symmetries and stabilities and collect them into a set of equations to solve for. Kitaev (Kitaev 2006 Appendix E) suggested that the algebraic combinatorics of the solutions to these equations can be formalized in the language of unitary modular categories.

The language of categories came about much earlier as a language of formalize analogous phenomena that occur in seemingly unrelated areas of mathematics. Recently, categories enriched with extra structure have been studied due to their flexibility in encoding certain data. Technically speaking, modular categories arose from the study of conformal field theories, which are a kind of quantum field theory that exhibit certain topological invariances.

The definition of a modular category is a bit complex; it is a ribbon fusion category with nondegenerate \( S \)-matrix. The interested reader can refer to Figure for a tree of what each of these terms imply. Each property/structure is interesting in its own right.

@startmindmap modularmap

skinparam backgroundColor transparent

*[#LightGray] modular

**[#LightGray] ribbon

***[#LightGray] braided

***[#LightGray] twist compatible with duals

**[#LightGray] fusion

***[#LightGray] rigid

***[#LightGray] semisimple

***[#LightGray] abelian

***[#LightGray] k-linear

***[#LightGray] monoidal

***[#LightGray] finitely many simple objects including unit

**[#LightGray] nondegenerate S-matrix

***[#LightGray] unit object is the only transparent object

@endmindmap

The reader might ask if the “braided” in Figure is related to the braiding discussed for anyons. Indeed it is, the braiding in a unitary modular category corresponds to braiding of anyons. There is an comprehensive dictionary of the correspondence between unitary modular categories and the physical interpretation of what the data represent. (A more detailed dictionary is found in Rowell and Wang 2018 Table 1).

| Unitary Modular Category | Anyon System |

|---|---|

| Simple object | Anyon |

| Tensor product | Fusion |

| Dual object | Antiparticle |

| Evaluation | Annihilation |

| Coevaluation | Creation |

| Unit object | Vacuum Sector |

| Twist | Topological Spin |

Classifying unitary modular categories up to some notion of equivalence is therefore equivalent to classifying systems of anyons. This is a difficult problem, but is thought to be possible, and positive signs have appeared. It was shown in (Bruillard et al. 2016) that there are only finitely many modular categories for a given rank. Physically, this would mean that a system \( n \) anyons can only interact nontrivially in finitely many distinct ways for each amount \( n \).

The ergonomics of modular categories can be challenging given the sheer number of equations to solve, but down-to-earth examples exist. Perhaps the most well known is \( \mathsf{Vec} \), the category of finite dimensional vector spaces. This is a rank \( 1 \) modular category with \( S \)-matrix \( (1) \) and \( T \)-matrix \( (1) \). Ok, not very interesting… This is indeed the most trivial example of a modular category, though more examples exist that are only slightly more difficult to understand. For example, the category of metric groups \( (G,q) \) is equivalent to the category of pointed modular categories. (Etingof et al. 2016, 8).

Despite the difficulty of classifying modular categories, this task enjoys deep connections to representation theory, quantum field theory, and condensed matter physics.

Conclusion

TQC is an exciting field gaining more and more traction as the years go by. Experimental evidence for topological matter with gapped phases earned Thouless, Kosterlitz, and Haldane the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2016. Microsoft has staked its entire quantum computing research division on the premise of TQC. The study of modular categories is advancing at rapid pace, and we are learning more and more about representation theory and quantum algebra along the way.